Remember those heady days of 2010? The release of the iPhone 4 and iPad, the New Orleans Saints won Superbowl XLIV, Iron Man 2 hit the cinemas, Eminem released Recovery, and Biden was Vice-President. It was also the year when camera shipments peaked at over 120 million units. How did the industry become the bit-part player it now is, shifting 9 million units just ten short years later?

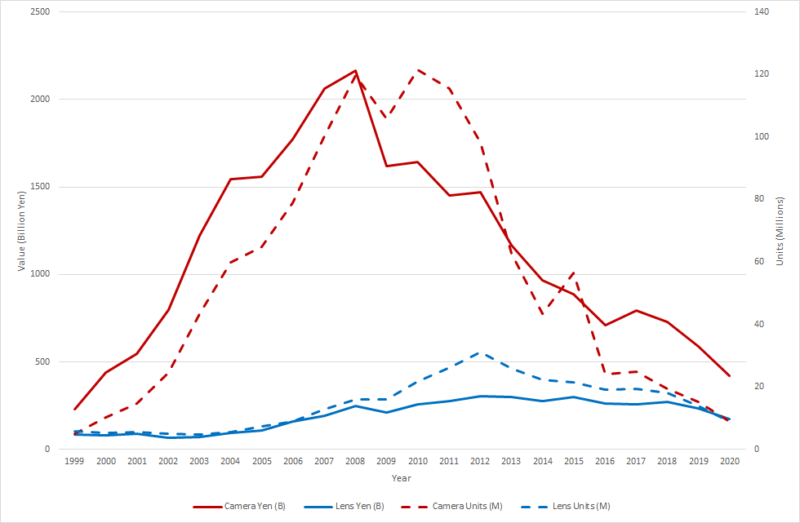

In terms of shipments and sales, 2020 really was a year to forget for the camera industry – annus horribilis – where it hit new depths that no one thought possible during those highs of 2010. Going from CIPA data of manufacturer shipments, we can see that 2010 just pushed out 2008 as the year to celebrate the fortunes of the camera with an inexorable rise from its base in 1999.

It must have seemed that anything was possible as factories popped up to produce ever more – cheaper – cameras to a mass market that was all too happy to buy them. Of course, the reality was perhaps a little more nuanced and cracks had already started to appear in the facade of an industry predicated on the mass market. If we factor in the value of those shipments, along with lens shipments then we can see what was really happening.

In fact, by 2008 the industry had already peaked in value; two short years later that amount had dropped by 25%. The writing was on the wall and while fable will point to the release of the iPhone in 2007 as the defining moment, that wasn’t actually the case. Sharp’s J-SH04 incorporated the first digital camera into a phone back in 2000 and by 2003 feature phones were outselling compact cameras.

It’s a salutary reminder that a product’s unique selling point (USP) has to remain, well, unique! In the case of the compact camera, that was an “adequate digital image” and phones subsequently plundered their sales.

This is what we might consider the classic boom and bust history of the digital camera going from nothing and potentially ending in nothing: the rise and fall of the camera industry. What’s interesting, however, is that flat trajectory for lens shipments, which hints at something else going on in the market.

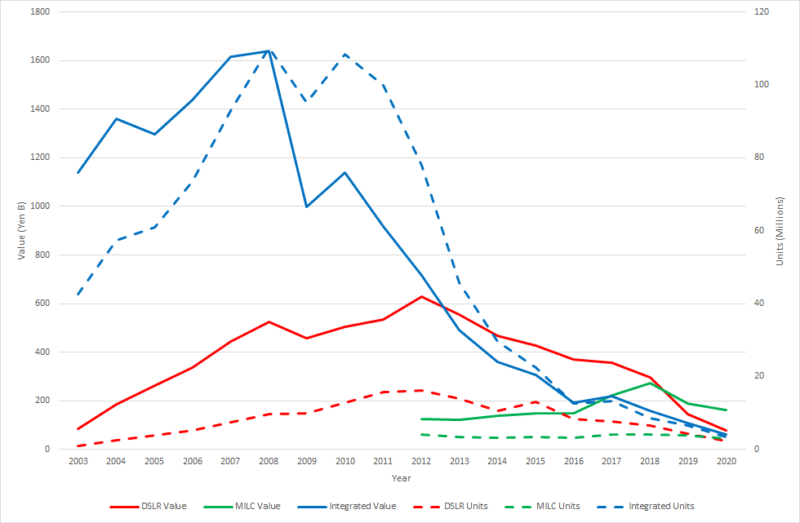

Crucially then, if we split shipments by camera type (DSLR, MILC, and Integrated) we see a different picture. Sure, it is still trending down but that boom and bust scenario is restricted to the Integrated camera and they are now only just shipping more than DSLRs and MILCs.

In fact, what shipment value shows is where the bulk of the money lies. In 2010, the sheer volume of Integrated cameras meant that that was where value lay, along with the profit. That is not true today where the value of DSLRs and MILCs now exceeds that of Integrated models. This has been the case for DSLRs since 2013, but their shipment numbers are genuinely in freefall and MILCs eventually exceeded them in value in 2019 and then unit volume in 2020.

The Rise of the MILC

The mirrorless camera – at least in its current guise – can be traced back to the Micro Four Thirds format and the release of the Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1 in 2010 although that was really a reboot of the 2003 Olympus Four Thirds E1 (minus the mirror box). After that, every manufacturer rushed up to the plate to present their variation of the mirrorless camera.

Quite why Panasonic, Olympus, and Sony came to market at that point with entirely new systems remains less clear. Sony had relatively recently acquired Minolta and was developing its camera business, while Olympus had singularly failed to transition effectively to manufacturing DSLRs. Fuji had had a similarly poor digital transition and was undergoing major restructuring as it came to terms with the death of film. Pentax had made a DSLR transition but lagged behind Nikon and Canon, who had very successfully moved into the digital era.

What is undeniable is that they were all making significant sums of money from selling Integrated cameras. The MILC was born out of an abundance of profit, combined with a number of manufacturers who were unsure what to do next.

The reason for the success of the MILC was more simple: Sony, Olympus, Fuji, and Panasonic achieved significant sales success. Meanwhile, Nikon and Canon had a vested interest in maintaining the DSLR market that was essentially sown up, but that gentle trickle of MILC sales turned into bubbling brook.

The writing was on the wall when Nikon and Canon pivoted to mirrorless in 2018, sounding the not-so-quiet death knell for the DSLR. This left Pentax swinging in the wind and – yes – releasing a new DSLR model in the form of the K-3 Mark III!

That said, the imploding shipments of DSLRs are a result of both customers choosing to buy MILCs and manufacturers reducing their shipments. There is no better sign that the market is finished as sales implode and substantial R&D ends; sure, we are likely to have old models sold for the foreseeable future in the same way the Nikon F6 persisted through to 2020, but new models are all but finished (although Pentax may still try to beat that drum).

What is the Future of Camera Sales and Shipments?

The key question for manufacturers going forward is what size is the market for selling cameras? Canon is a little pessimistic on this point believing it will naturally fall be below 10 million units, COVID excepting. To better understand the digital future, we need to understand the analog past.

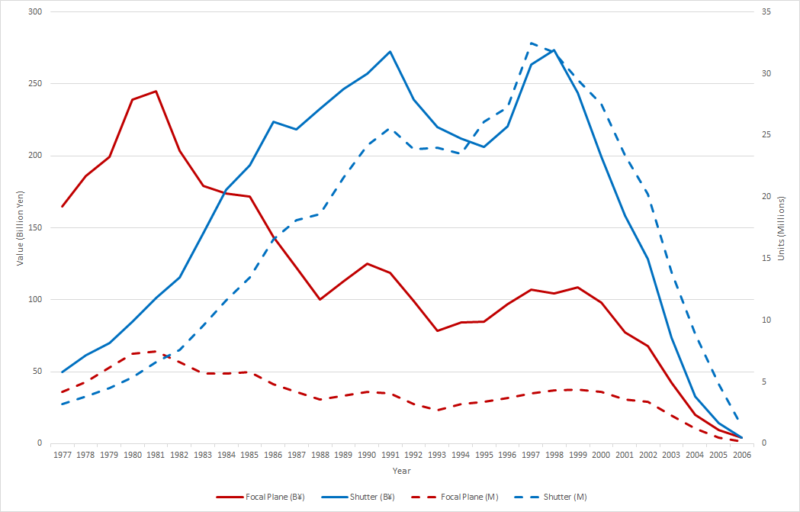

Again using CIPA data, we can see that focal plane shutter models (ILCs) peaked in 1982 at 7.5 million units, but what’s remarkable is the ¥230 billion (~$2B) in value this represents (not adjusted for inflation). With the rise of the compact camera (“Shutter” models) and mass-market consumption, we can see that total shipments eventually reached 36 million, but their value was on a long-term downward path as the mantra of “pile it high, sell it cheap” took hold.

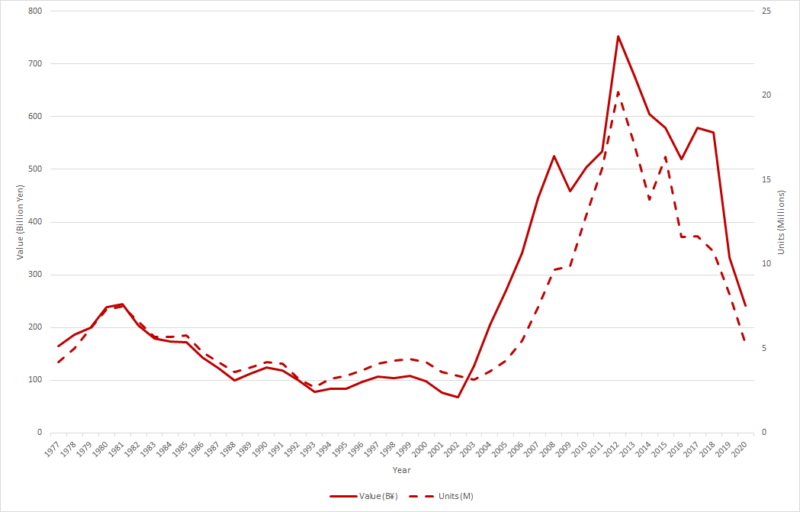

What’s more instructive is understanding the underlying professional and amateur market and looking specifically at interchangeable lens models; the graph below combines together the film and digital figures (again not adjusted for inflation).

And this tells the remarkable story of the digital boom which took the historic baseline of around 4 million annual shipments of film cameras and pushed it up to 20 million by 2013. That volume has been in freefall since, but Canon’s expectation that this value sits somewhere between 5 and 10 million is probably about right.

Value is more difficult to gauge because of the effect of inflation, but since 1980, goods in general have increased in price by about x2.5 which probably means that the total value of the market – about ¥230 billion – is more or less the same as today.

So where does that leave us? Probably back where we started in the 1980s! Cameras have always been an emergent, expensive and, as a result, high-end tech sector. The first (analog) consumer boom came in the 1980s because film cameras could be manufactured very cheaply, with the mass-market scale used to minimize the cost of film, development, and printing. The second (digital) boom of the 2000s took advantage of microelectronics, miniaturization, supply chain sourcing, and just-in-time manufacturing.

Both booms came during periods of relative consumer wealth. Film’s mantle was stolen by digital which was subsequently lost to the smartphone, but the underlying system camera sales have remained surprisingly stable.

The camera sector remains a bit-part player in the global market place and manufacturers need to work out how they are going to make it pay for itself. Sony, Canon, and Fuji have largely been successful in achieving this, all in different ways but with their camera divisions subsumed into much larger organizations.

Significant question marks remain as to whether Olympus can survive and only time will tell. The fortunes of Pentax and Panasonic within their respective conglomerates remain to be seen.

Nikon is an anomaly here because it is relatively small as a business yet still reliant upon its camera business. It is unlikely to fail commercially, but what it looks like as a business in 10 years’ time will be fascinating.